[This is the second and last -- for now -- in a series on environmental politics. I've decided to combine the second and third topics in the series in one column.]

FLAGSTAFF, Arizona, February, 2003 -- This dirt road used to be one of the most lightly-travelled in northern Arizona.

Now, it's not travelled at all -- at least not by any kind of motorized vehicle. About a year ago, the United States Forest Service (USFS) decided to close almost all of Coconino National Forest to vehicular traffic, except on maintained, numbered Forest Service roads.

The extensive network of small dirt roads, paths, and trails such as the one pictured above were closed to all vehicular traffic.

That sounds great, on the surface -- why not protect public land from damage caused by off-highway vehicles, from tire tracks, air and noise pollution, and generally from being degraded by fossil-fuel-burning machinery?

Well, it does seem obvious that locking out dirt bikes, quads, and cars is of unequivocal benefit to everyone -- but as I tried to illustrate last May (in "Global warming -- real climate change, or just hot air?", 5/19/02), what's "obvious" isn't always true.

I used to see a dirt bike or two in the forest once in awhile -- always on the trails, never causing harm.

Take the local example -- it's from a small piece of the Coconino National Forest that's right behind Country Club Caverns, the apartment complex where Meg and I lived from late 1999 until December of last year. (Well, officially, the place is called Country Club Meadows, but we called them "the Caverns" because the apartments were unnecessarily dark and airless. Lousy design, but that's beyond the scope of this column.)

I used walk our dogs, Chloe and Zelda, on the Forest Service land at least once or twice a week. Before the vehicle closure took effect, I used to see a dirt bike or two out there once in awhile -- once in a great while, that is. I'd say that in two years of dog-walking, I probably saw motor vehicles -- and they were always on the trails, never trampling vegetation or causing any kind of harm -- once every three months or so, on the average.

Nonetheless, because of threats of litigation by environmental groups, the Forest Service made a decision, in the fall of 2001, to close most of Coconino National Forest to motor traffic of any kind. This included the piece of land behind our apartment. One day, a sign appeared at the forest entrance:

I hoped the environmentalists were satisfied, at that point. They had succeeded in reducing recreational opportunities for local residents who enjoy taking a spin on their dirt bikes -- and maybe, occasionally, kicking up some dust in the process.

However, the closure did nothing in terms of environmental protection. That's because the dirt bikes were doing nothing in the way of environmental damage in the first place. In fact, what they did mostly was to help keep the trails open and free of vegetation -- benefiting those of us who just like to take a stroll through the forest and not get thorns in our socks.

I don't know which environmental group or groups were specifically responsible for the Coconino National Forest closures -- it wasn't clear, from the materials I got from the Forest Service, why they were closing the acreage. (I did take advantage of the opportunity to submit comments to the USFS district office, during the public-comment period that preceded the closure. They didn't listen, but I did get my comments in.) In the Flagstaff area, there are a lot of tree-hugging groups -- and some of them do good things; the Sierra Club, for instance, was a major player in the successful movement to close a pumice mine on one of the San Francisco Peaks a couple of years ago.

However, I think what's going on here is environmental politics, not environmental protection. The Forest Service knows that off-highway vehicle (OHV) recreation is a politically incorrect activity -- it seems obvious (there's that word again) that OHVs are bad for the forest, and that they cause erosion as well as air and noise pollution. No one likes them, except for the people who ride them.

That being the case, closing huge areas of National Forest land is an easy, cost-free way for the USFS to score political points and get the environmental groups off its back.

Grip it and rip it!

But apparently, merely closing the forest trails wasn't enough. So last fall, the Forest Service went further. One day, when I took the dogs for a walk in the forest, I came to what you see here; namely, the end of the road:

As you can see, some sort of enormous piece of equipment was brought in, to rip up the dirt road and render it unusable. Where the road used to look like this,

it now looks like this:

Obviously, it took a pretty serious piece of machinery to do the job -- probably something like an enormous roto-tiller. Some of the boulders in this photo were at least three or four feet in diameter and must have weighed several hundred pounds each.

I'm not sure what the Forest Service thought it was accomplishing. Although this dirt road is obviously impassable, the only motorized vehicles I'd ever seen in this part of the forest were dirt bikes and quads; always, without exception, traveling on the roads and trails.

If any illicit riding is now going on in this part of Coconino National Forest, it's happening on virgin ground. However, the Forest Service can say, "Look at what we've accomplished; we've taken all the dirt roads and trails out, restoring the land to its natural state," or some such nonsense.

No fun allowed, unless it's our kind of fun

The closure of National Forest lands to motorized public recreation hasn't accomplished a thing, in terms of actual environmental-quality benefits -- the forest behind my old apartment building used to be in fine shape, and as far as I can tell, it's still in fine shape (except for the destruction caused by the big roto-tiller).

However, the closure reduced the number of public-land areas that are available to people who like to engage in the legal activity of riding dirt bikes, quads, and other OHVs. These people -- who, by the way, pay for the right to ride off-road, in the form of taxes and the permit fees that are required of all OHVs in Arizona -- now have fewer places to ride. That results in heavier use, and more environmental degradation, in the areas that are still legal.

This, of course, provides fodder for the environmentalists to say, "Look at all this erosion; we really need to close these areas!" So more riding areas are closed, which results in still more pressure on the few areas remaining open, and the cycle continues -- until eventually, off-road recreation is banned altogether. Meanwhile, scenes like this are considered not environmental degradation, but environmental restoration:

Now, I'd be the first to argue that particularly sensitive areas, especially if significant damage has been documented, should be closed to OHV use. There are areas where dirt bikes do actually cause a lot of erosion, or where they just shouldn't be going. But the problem is that the Forest Service takes a sledgehammer approach -- instead of closing areas that need to be closed, they arbitrarily close huge amounts of land, regardless of whether or not there's any need to do so. Instead of identifying specific areas that need to be protected, they just fence off the whole thing -- that way, they can say, "Look how many millions of acres we protected this year," even if most of those acres weren't threatened to begin with.

The mass land closures were particularly bad during the Clinton administration. His "Roadless Initiative," which affected almost 60 million acres of Federal land in the West, was billed as a measure to protect pristine wilderness by banning roads.

The problem is that a lot of the areas were far from pristine, weren't wilderness, and weren't even roadless to begin with -- the initiative simply banned maintenance of existing roads and trails and mandated closure of huge areas to motorized recreation.

Monumental stupidity

In addition to the acreage covered by the Roadless Initiative, Clinton created several huge National Monuments (administered by the National Park Service) in Utah and Arizona. Again, off-road recreation is banned in these areas. The justification was that these remote regions were somehow "threatened" by mining or logging interests, and that declaring them off-limits to everyone except hikers was the only solution.

These land closures are pure political grandstanding. They sound great to suburban "environmentalists" on the east and west coasts -- people who only go to a National Forest once a year, when they're on vacation -- but if you actually live out here and see what kinds of land they're closing, it becomes apparent what's really happening.

Why does this happen? For one thing, motorized recreation is an easy target. It doesn't really serve much of a useful purpose, other than to provide enjoyment for the people who do it. And the idea that it causes significant damage is one of those obvious-but-wrong canards of which the environmental movement is so fond.

The other problem is that there's no big money behind motorized recreation -- so there's not much standing in the way of land closures. (There is some small money, however. If you're interested in preserving public access to public land, you might be interested in the work done by the Blue Ribbon Coalition, a group that seeks to keep public lands open for recreation. Disclosure statement: I'm a member.) The Greens can't stop big money from doing what it wants to do -- primarily, putting up luxury housing, private golf communities, and so on -- so they take what they can get. If they can't stop a gated community, they'll settle for locking out some dirt bikers. At least, that's what's been happening here in Flagstaff.

Save the noxious weeds!

Besides dirt bikes being an easy target with no political clout, let's face it: the Greens just don't like people who burn gas, and they'll do whatever they have to do to give us a hard time about it.

Their favorite tactic is to find an endangered species that lives in an off-road riding area and file a lawsuit to "protect" it. In the Imperial Sand Dunes Recreation Area (CA), the Center for Biological Diversity (the same group that filed lawsuits to prevent forest thinning on USFS land, which led directly to the catastrophic 400,000-acre fire in Arizona this year -- but I digress) sued the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) on behalf of Pierson's Milkvetch, a poisonous weed that inhabits portions of the recreation area. Rather than fight the litigation, the BLM caved in and closed 48,000 acres to OHV use.

The Sierra Club's Web site claims that the closure is a victory for those who want to protect "rare wildlife" from "off-roading mobs." Well, I happen to share an office with someone who regularly visits the Imperial Dunes on weekends, to indulge in a little berm-blasting and dune-dusting. I can't speak to the characteristics of Imperial Dunes enthusiasts as a whole, but my office-mate is a polite, well-behaved individual who belongs to a religious denomination that bans smoking and booze -- and by all accounts, their behavior on the dunes is highly civilized.

The Greens get one area after another closed off, until eventually the whole Great Outdoors is closed to trail riding, as it is in Europe.

The Sierra Club claims that the Dunes are host to "unmanageable crowds which have grown to 200,000 on some weekends." Well, I understand -- from what my office-mate tells me -- that people do come from hundreds of miles around, on certain weekends, to ride on the Dunes -- but most of that is due to exactly what I was getting at earlier: the fact that so many other areas have been closed. The Greens get one area after another declared off-limits, which puts more pressure on the remaining open areas, which begin to show signs of over-use, giving the Greens an excuse to lobby for their closure, ad infinitum. Until the whole Great Outdoors is closed to trail riding. (Don't laugh -- that's pretty much the way it is in Europe.)

And to what end? The fact is that off-highway vehicles just do not cause much damage, in most areas. They do cause a certain amount of erosion, they make some noise, and they burn gas -- but on the scale of environmental hazards, they're not even a blip on the screen. So why ban them? Because they're an easy target and a cheap way to score political points with suburban Greens who know only what they read in environmental propaganda.

Where there's a real need, sure, close trails. Ban OHVs where they don't belong. I'm all in favor of that (being a card-carrying member of The Nature Conservancy, as you'll recall from my last column). But the mass closing of taxpayer-owned lands, for no reason other than political posturing, is bad policy.

Water this!

One more misguided environmental bromide, before we go. This is the idea that the Colorado River is overused and that it's unrealistic for cities like Los Angeles, Las Vegas, and Phoenix to expect that they can continue growing like weeds and depending on the Colorado for water supply. But isn't it obvious, I hear you saying, that the Colorado can't possibly have enough water to keep those cities going.

Well, actually, it can. The fact is that the biggest users of Colorado River water aren't cities at all: they're farms, like this one:

This picture was taken about 10 miles north of Blythe, California -- the mountains visible in the distance are across the river in Arizona.

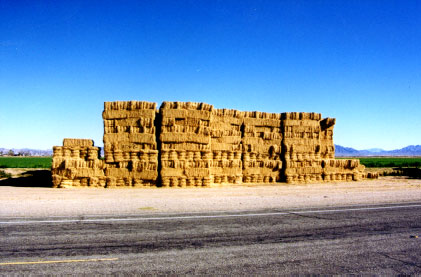

Similar farms line the Colorado all along the California shoreline (as well as in other states along the river). What are they growing? For the most part, low-value crops like alfalfa:

Other crops include lettuce, leaf lettuce, carrots, sugar beets, cantaloupe, and onions. Cattle ranching is also a major economic activity in the area. (This information comes from the Imperial Irrigation District's Web site -- the District is a public utility that provides water to California's Imperial Valley.)

All in all, farming accounts for roughly 80 percent of Colorado River usage. This amounts to upwards of a trillion gallons a year. That's trillion, with a tr.

What does this say? It says that the Colorado isn't short of water -- not by a long shot. What we have is a water-rights problem. A Western truism holds that "Water flows uphill, toward money." Recently, San Diego has been negotiating to buy water from the Imperial Irrigation District -- essentially, they want to buy water rights from farmers and use the water for urban drinking-water supplies.

This is what's eventually going to happen throughout the Southwest; water will be diverted from agricultural to urban use. People who live in the cities are going to shell out a lot of money to buy the water. But that's as it should be -- I like onions and cantaloupe as much as the next person, but why should we be growing them with huge amounts of river water, in areas that get two or three inches of rainfall a year, like the Imperial Valley?

Alfalfa vs. golf

Once again, the environmental groups who say, "The Southwest's water situation is an environmental disaster" have got it wrong. There is no water supply problem in the Southwest; just a distribution problem -- which will eventually be solved by market forces. Instead of having 80% of the Colorado used for agriculture, farmers can go elsewhere, to lands where there's more rainfall. Using a trillion gallons of water a year to grow alfalfa makes no sense at all.

Now, having said that, it would be disingenuous to ignore the fact that there are some other pretty illogical water-use patterns in the Colorado usage area. A few weeks ago, Meg and I visited a friend who lives in Palm Springs, which is in California's Coachella Valley -- an area that gets something like three inches of rain a year. Palm Springs was originally a desert oasis, with natural sources of groundwater that belie the region's desert climate. But the local water is nowhere near enough to support the more than 100 golf courses that have been built -- those, like the alfalfa farms, are irrigated with water from the Colorado.

Are Western cities going to be in big trouble because of a lack of water? No -- they simply are not.

Another environmental disaster? Well, no -- it's just another case of "water flowing uphill toward money." The high rollers who escape from L.A. and buy into the gated golf communities of Palm Springs, Rancho Mirage, and La Quinta are willing to pay for the infrastructure to bring water in from the Colorado.

As an old geography major, I'm a little revolted by the artificiality of the place -- and as an old leftist, I'm a little disgusted with the wretched excess (although I have to admit, there's some terrific golf to be played in the area; our hostess sent me out for a round on a Pete Dye course that goes right by her back patio, and I have to confess, I enjoyed the day immensely).

Again, the Colorado has plenty of water to support such things, as long as people are willing and able to pay for them.

Should the water cost more? Perhaps. Should government agencies "do something" to prevent people from piping water dozens of miles to irrigate golf courses in expensive gated communities in the desert? I don't see why. (Should the Federal government change our state water allocations and allow more water to reach Mexico? Yes -- but that's a separate issue. Again, it's not that the water isn't there; it's that it isn't allocated properly.)

And are Western cities going to be in big trouble because of a lack of water? No -- they simply are not, at least not in the near future. Because -- as with the other environmental issues I've discussed in this series -- what seems "obvious" is not always true. The Colorado is adequate to supply a lot more people than currently live in the Southwest. Timothy Egan, in his excellent book, Lasso the Wind: Away to the New West, argues that the population of Phoenix could grow to somewhere between two and three times its present size before it would run into serious water problems (other than simply the cost of buying water from farmers).

There are a lot of serious environmental issues out there -- air pollution, solid waste disposal, drinking water quality, and possibly, atmospheric issues caused by ozone, carbon dioxide, and other gases. Protection of natural geographic features is important. Endangered species need protection. The list goes on and on.

But it's essential to spend some time evaluating each issue individually, instead of chasing the latest "crisis" and making policy decisions based on what seems obvious. This leads only to bad policy (operating on the assumption that "global warming" is an established fact, which it isn't), political posturing (closing public lands merely to appease extremist environmental groups), and public planning based on erroneous assumptions (imagining a crisis of water supply in the Southwest, when it's merely an economic problem).

Copyright © 2003 Kafalas.com, LLC

Feedback? Fire off a letter

to the editor, and I'll post it on the letters

page. Letters may be edited for clarity or length.