My geography

book, and why it'll never happen

PROVIDENCE, Rhode

Island, February 17, 2007 -- As an old geography

geek, I'm one of those people who love to stare at maps. And when

I look up at the sky, I don't see pictures of sea creatures, unicorns,

or whatever most people imagine -- to me, the clouds always end up

looking like countries and continents. "Hey, that one's a good

Scandinavia,"

I'll decide, "and there's an Africa, which fits in pretty well with the

South America over there!"

Anyhow, I've also always had a fascination with the map of the United

States, how states came to be in odd the shapes they're in, and how the

borders got to be where they are. Some are defined by

geographic features -- usually rivers. For example, New Hampshire

and Vermont are separated by the Connecticut River (for the most part;

there's a small section where that's not the case -- but I'm getting

ahead of myself), and California and

Arizona are separated by the Colorado. That sort of thing.

But then, take a look at the border between Illinois and Indiana.

Most of the way down, it's a straight north-south line, and then, just

southwest of Terre Haute, it begins to follow the Wabash River, from

which point the river and the border coincide all the way down the two

states. Almost, that is.

There are pieces of

Indiana that are on the "wrong" side of the Wabash, over with Illinois,

because the river moved.

If you look closely (easily accomplished with a hybrid map/photo on

Google Maps or other satellite mapping tools), you can see that the

border does not follow the current

course of the river -- it follows where the river used to go but

doesn't anymore. Just south of York, IL, there's a place where the

border jogs east for a mile or so, then bends south and back to the

west, rejoining the river about half a mile south of where it

departed. The river used to meander to the east that way, but

because of erosional processes that caused it to change course and take

a shortcut, it now goes south. The border -- going along the old

course of the river -- cuts through an area of some trees, then through

what we geography geeks call an "oxbow lake" (a cutoff meander that

used to be part of the river but is no more) and back out to the

river's current path.

We're cut off!

There are a

few other places where the border does the same thing -- the border is

a fixed line, but the river is not. There are also a few places where

you can tell that it's going to happen again (exactly when may depend

on how effective manmade attempts to constrain the river with levees

might be at delaying the inevitable) -- a piece of Illinois that is now

together with the rest of the state, on the West side of the Wabash,

will get cut off, and it'll end up over with Indiana, on the east side,

when the river changes course again. Predictably, there are also

pieces of Indiana that are on the "wrong" side of the Wabash, over with

Illinois, because the river moved. Further down, after the Wabash

joins the Ohio, the same thing happens with the border between Illinois

and Kentucky; the Ohio, like most rivers, meanders over time, and parts

of each state get cut off from the rest of the state. The same

thing happens along the Mississippi, between Illinois and

Missouri. The village of Kaskaskia, IL is on the west side of the

river, cut off from the rest of the state. Wikipedia provides a

short description of how that happened:

Most of the town was

destroyed in April of 1881 by flooding. In that month, the Mississippi

River, which then served as the state's western border, cut across

an oxbow and carved a new channel through much of the former

town. The people of Kaskaskia, startled to find themselves on the

Missouri side of the river, demanded that the state boundary conform to

the old

channel. Kaskaskia is therefore one of the few portions of Illinois

west of the Mississippi. The state boundary line follows the old

riverbed, now a creek or bayou.

That's an example

of some material that would go into a book that, for years, I've wanted

to write: The State Borders and How

They Got That Way. Other examples include the Kentucky

Bend, Minnesota's Northwest Angle, and one that had piqued my

curiosity for a long time, the Southwick

Jog in Massachusetts. Full discussion of each of these would take

more time than I have this weekend, and would also require travel to

each location to obtain ground truth. These days, you can do

quick-and-dirty research on just about any subject with Wikipedia and

Google Maps. If I were to sit down and make an attempt to

actually write the book, these sources would undoubtedly be my first

cut at each state border area, followed by on-the-ground research at

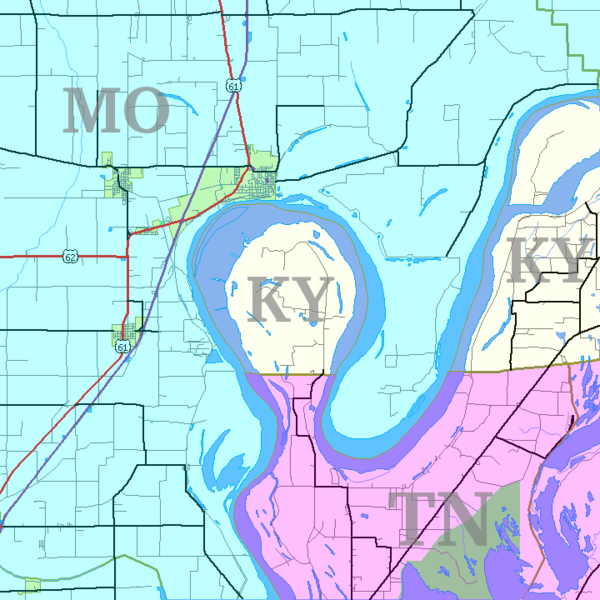

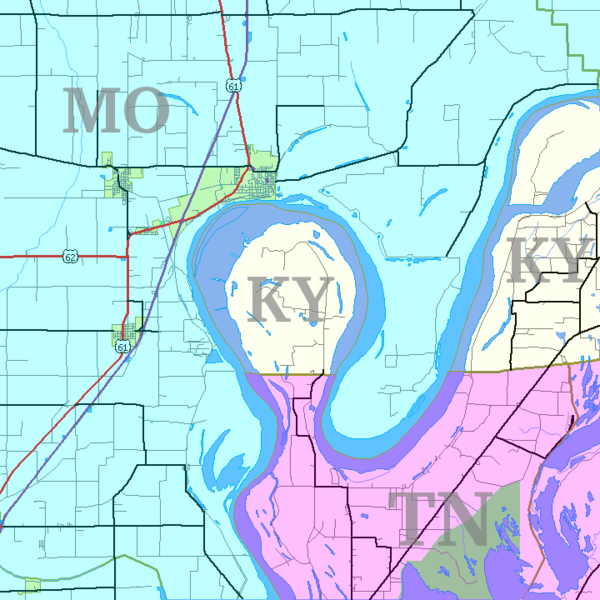

the sites themselves. This image of the Kentucky Bend, from

Wikipedia, illustrates what I'm talking about:

What's even more interesting -- albeit probably just in a time-wasting,

geography-geek sort of way -- is to picture what the map will look like

in the future, after the river changes course again and cuts off the

Kentucky Bend from the south. Let's assume that the river takes the

shortest path, cutting across at what is now the narrowest point of the

peninsula that includes the Kentucky Bend. If that happens, it'll

probably cut off a tiny bit of Tennessee along with the Bend, attaching

them to Missouri by land, and leaving the map with tiny bits of

Kentucky and Tennessee

isolated from the rest of their states.

Get out there!

(Doing all of this

on-line sounds too much like cheating -- and it's also dangerous, as

the Wikipedia article on the Southwick Jog contains erroneous

information, which I discovered by reading the article by the Rev.

Edward R. Dodge that is linked from Southwick's site. Rev.

Dodge's 15-page article on the Southwick Jog is quite well researched

and delves into a lot of Colonial history -- because that information

is essential if you want to understand how Massachusetts and

Connecticut determined their borders, why the border between them was

in dispute for so long, and how the Southwick Jog came into being as a

way of resolving the matter. Now, have I piqued your interest

enough to make you go off and read Rev. Dodge's article? Once

you're done with this one, that is.)

The further down the Lower Mississippi you go, the more frequent -- and

strange-looking -- the border jogs, to the point where

there are many small sections of Mississippi and Louisiana that are on

the "wrong" side

of the river. In any case, you see what I'm getting at. The state

borders, while looking fairly obvious at first glance, are anything

but. When you start taking a look at where the lines actually

are, you start asking a lot of questions. And when you start

delving into the history of how the lines ended up where they are, it's

not as simple as you'd have thought -- or at least as I'd have thought.

The State Borders and How They Got That Way

is not going to get written, because it's too big a subject!

I should also add

that my intent here is not to trivialize or make fun of these

geographic oddities. Often, when a big river like the Mississippi

changes course, it's because of catastrophic floods -- and in the case

of the Kentucky Bend, there were also land and jurisdictional disputes

that resulted in people being shot. In other cases -- for

example, the centuries-long border dispute between Massachusetts and

Connecticut that led to the eventual deal involving the Southwick Jog

-- the main issue was money. To be more specific, tax

money. The general rule seems to be that a town does not change

states because the river moved -- if that happened, the "new" state

would get tax revenue from the town it acquired. That, as far as

I can tell, is the main reason why you get these funny-looking borders

along meandering rivers. Where a border dispute is caused by a

surveying error (as in MA/CT), no state wants to give up tax revenue

just because the state line may have been drawn in the wrong place and

is being corrected at a later date. But in any case, when you

start delving into the history... it turns out that there's a lot of

history to delve into.

That's why The State Borders and How

They Got That Way is not going to get written; it's too big a

subject! Well, it's also probably not of interest to enough

people to get a publisher to pay someone like me to travel around the

country for a few years and interview all the state, city, and county

officials, local historians, and crusty old-timers in rocking chairs to

find out the history of exactly how and why each jog of the border got

to be the way it is. But it would make for great reading, if I

(or someone better-qualified) had the time to write it....

Copyright

© 2007 John J. Kafalas, except the Wikipedia image, which is in

the public domain.

Return

to the home page